Am I Marmite?

8 minutes read

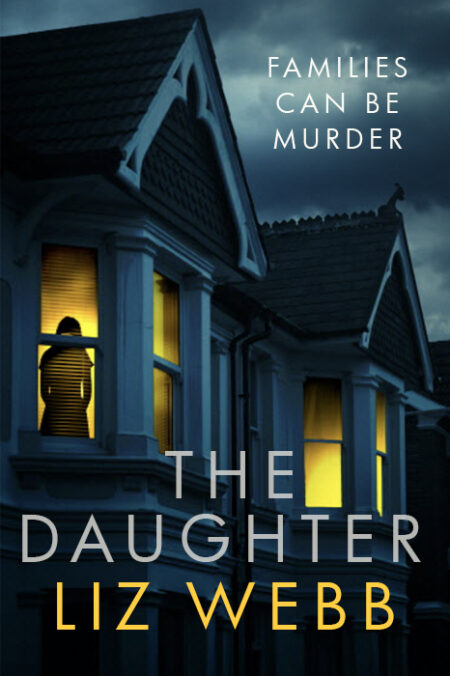

‘Loved it,’ said a friend who’d just read a proof of my debut novel, The Daughter. ‘But how did you come up with that main character?’

‘Oh, well, she’s me,’ I replied, with a self-deprecating little laugh that implied, Oh goodness, I don’t want to blow my own trumpet, but of course the quirky, charismatic main character in my brilliant debut novel is totally me.

But disconcertingly, my friend didn’t smile back at me in admiration. She raised her eyebrows and snorted. ‘God I hope not,’ she said, with a roll of her eyes, as if to say: Lordy, just imagine if you were admitting to being THAT awful.

Whoopsie daisy, backtrack, backtrack, backtrack.

‘As if,’ I countered with a shrug to imply: Nooooo of course not. I just took something bleak I once heard someone say on a bus, and took a huge imaginative leap to create a character who thinks like that all the time.

But who was I kidding? I was flat-out lying because I couldn’t face my lovely friend thinking ill of me. Hannah, the lead character in my book, thinks like me. Although she acts in considerably more extreme ways than I ever have, as the totally made-up plot spirals towards its high-octane conclusion, lots of her thoughts are actual thoughts that I’ve had. As a first-time novelist, as many first-time novelists do, I’ve based my main character’s voice on the way I think… sometimes… okay a lot… no just occasionally… oh what should I say that you’ll think well of me… please still like me.

I started The Daughter on the excellent Faber Academy six-month course Writing a Novel in 2019. We were encouraged to find a ‘distinctive voice’ and as an ex-stand-up comic, I found myself naturally drawn to a first-person narrative voice and one that was darkly quirky. But I was writing a ‘character’. Wasn’t I? My heroine Hannah comes from a splintered family with a very dark secret, and as the book progresses, she starts to impersonate her dead mother to solve her murder. None of that is in my bio! But I can’t deny that the voice – dark, sarcastic, self-doubting and driven – does have more than a hint of me in it.

My friend’s reaction wasn’t that left-field. When my agent was touting my book, she got a mix of reactions. Some publishers said nice things but were unsure if they ‘quite liked the main character’. Luckily other (very discerning) publishers loved her, in Germany, Norway and Serbia, where my book first sold (interesting and unnerving that I appealed initially to residents of cold countries). Then I got four offers in the UK. People who loved Hannah, really loved her. But until I tried to sell the book, it had never occurred to me that she might not be universally likeable, because… well, she’s me.

I now realise that I have created what people refer to as a ‘marmite’ character – one who you either really click with or you really don’t. I’ve also realised that I’m so pathetically desperate for acceptance, that I’ll adjust how I talk about my character according to how other people start talking about her. If they like her, I admit to some of her being based on me. But if they don’t, I find myself spouting total rubbish about how I just plucked this prickly dark character from the ether.

She’s also not me in many ways – purely physically for instance: she’s tall, skinny, beautiful and 37. I’m 5 ft 1; no-one of even the kindest myopic mindset could call me skinny; I have what is a euphemistically called a ‘lived in’ face; and I’m older than 37 by 3 plus 4 divided by 2 plus a bit more. But in writing this book, I have to admit that I’ve put a me-like character into extreme situations and written about what I would think and do under that pressure. So, I’ve been genuinely wrong-footed when some people say that my main character could be viewed as dislikeable. While I’m totally able to indulge in hefty wads of self-loathing, I don’t think I’m totally dislikeable.

When I started sketching out possible scenarios for my second book, which I’m in the middle of writing now, I began one possible synopsis with a character who was, shock horror, ‘having an affair’. I haven’t actually done that myself, (okay, several long kisses at The Edinburgh Festival, which I did admit straight away to my boyfriend at the time, who then dumped me), so this character would have needed more imagination from me. But I was warned off. ‘Oh, do be careful of making her dislikeable again,’ said the lovely friend. Well, side point, are people who have affairs inherently dislikeable? But putting a pin in that, I do want to learn from previous reactions. The question is, should I, and indeed can I, write an implicitly ‘likeable’ character? I’ve no idea how 100% likeable people think. I remember talking with an equally flawed friend at work as we looked across at one of our colleagues, who was a lovely, year-round-sunny person, who seemed to actively ‘mean what she said’ with no subtext. We used to look at her in wonder and whisper to each other: ‘My God, she’s unreal, she must have had a—’ voice lowered even further in disbelief, ‘happy childhood!’

I’m not in any way, shape or form comparing myself to the wonderful writers I’m about to mention, but marmite characters are a well-trodden literary path. Many of my very favourite lead characters are seriously flawed and tetchy in the extreme: the brilliant Libby Day in Gillian Flynn’s wonderful Dark Places; the eponymous heroine of Elizabeth Strout’s masterpiece Olive Kitteridge; or, (and yes she is a serial killer, but I still really warm to her) the fantastic anti-hero Rhiannon in C J Skuse’s Sweetpea. I have no proof, but I wonder if there is a smidgeon of the authors’ personalities in those brilliant characters.

So, if my character is marmite and she’s based on me, then I have to face the question: am I marmite? It’s not a question I thought I’d be asking when I wrote my first novel. I thought that my career trajectory had gradually removed me and my personality from the spotlight: I was originally a stand-up comic, so of course I and all my quirks were totally on display; next I worked as a radio producer and felt much less on view, directing actors through thick sound-proofed glass; then when I became a novelist, I thought that I was finally totally private and only my words would be dissected. But I’ve put too much of my own character into Hannah for this to be realistic.

However, the truth is, whatever I’d written, whether I admitted it or not, there would always be part of me in my writing, because it’s my writing. And even if I’d written something as far away from me and my thoughts as is feasibly possible, readers would still imagine that something in the book gives away something about me. I could have written a book from the point of view of a bullethead parrotfish on the Great Barrier Reef, saying ‘and as I go to sleep, I surround myself with a cocoon of my own mucus’, and some reader somewhere would think I wonder if Liz does that too.

So, I really hope that lots of people will like the flawed heroine in The Daughter and, by extension, me. But if you don’t like her, then… she’s nothing like me, a total figment of my imagination.

I lean in and whisper the question I have never let myself utter in twenty-three years. “Dad, did you murder Mum?”

Hannah Davidson has a dementia-stricken father, an estranged TV star brother, and a mother whose death opened up hidden fault lines beneath the surface of their ordinary family life. Now the same age that Jen Davidson was when she was killed, Hannah realises she bears an uncanny resemblance to her glamorous mother, and when her father begins to confuse them she is seriously unnerved.

Determined to uncover exactly what happened to her mum, Hannah begins to exploit her arresting likeness, but soon the boundaries between Hannah and her mother become fatally blurred.

The Daughter will be published in hardback, ebook and audio on 19 May 2022. Pre-order it here.

Liz Webb was a stand-up comic for ten years performing at clubs across the UK and at festivals in Edinburgh, Newcastle, Leicester and Cardiff. She also worked as a prolific radio drama producer for the BBC and independent radio production companies, before becoming a novelist. She lives in North London with her husband, son and serial killer cat Freddie. Visit her website or follow her on Twitter here.

End